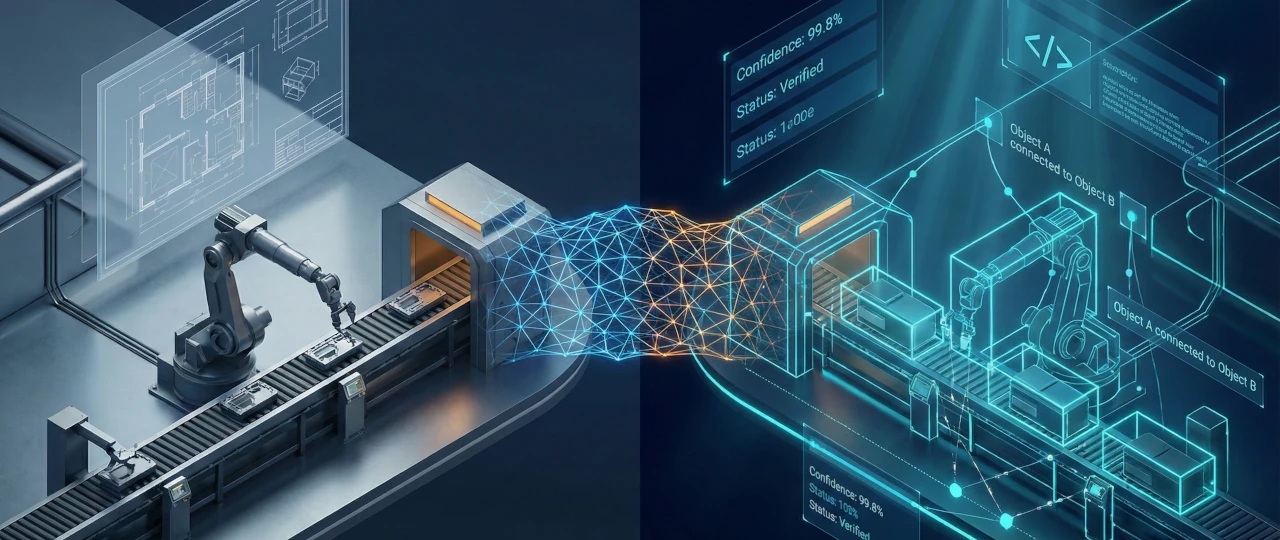

For years, enterprise software has operated in the dark. It could process rows in a database or strings in a text file, but the physical world – the factory floor, the scanned schematic, the live video feed – remained opaque, accessible only through the bottleneck of manual data entry. That era of blindness is ending.

The convergence of Large Language Models with advanced computer vision has created a new class of infrastructure capable of not just "seeing" pixels, but "reasoning" about them. We are witnessing the transition of visual AI from a stochastic novelty into a deterministic utility.

However, integrating "eyes" into the enterprise stack is not merely a software update; it is an architectural overhaul. It demands a confrontation with hard engineering realities: the bandwidth costs of 24/7 streaming, the hallucinatory risks of probabilistic models, and the "dark matter" of unstructured data that defies traditional indexing. This guide explores the transition from experimental pilots to industrial-grade visual intelligence, mapping the technical decisions required to build systems that see, think, and solve.

Computer Vision is No Longer Experimental, it's The New Business Infrastructure

Computer vision has transitioned from a captivating R&D capability to a strategic asset for industries dealing with the physical world. While early iterations were often relegated to experimental pilots, today's technology offers a practical pathway to digitize physical environments for sectors like manufacturing, logistics, and healthcare. For these industries, the technology is evolving into a significant operational driver, offering a real opportunity to automate visual tasks that were previously impossible to scale.

The global market reflects this maturity, valued at approximately $20.75 billion in 2025 [Fortune Business Insights. (2024) https://www.fortunebusinessinsights.com/computer-vision-market-108827] and projected to grow at a compound annual growth rate of 14.8% through 2034 [Roots Analysis. (2025) https://www.rootsanalysis.com/computer-vision-market]. For decision-makers, this growth signals that computer vision (CV) has graduated from a speculative bet to a reliable tool for converting visual information into structured, actionable data.

It bridges the gap between physical operations and digital intelligence, allowing organizations to optimize processes that were previously opaque or reliant on manual oversight. Crucially, this technology enables visual information to serve as a primary input for other AI systems, effectively expanding the utility of artificial intelligence beyond the text-based inputs that characterized the early phases of the AI boom.

The 2026 Market Context

As we move through 2026, the conversation surrounding computer vision has shifted fundamentally. The initial rush of pilot programs and experimental deployments has settled into a more mature understanding of the technology's role. Organizations are no longer asking if the technology works – the detection rates and processing speeds are largely proven – but rather how it integrates with existing enterprise architecture to solve specific, high-value problems. This maturity is characterized by a move away from generalized "AI initiatives" toward targeted deployments where visual data solves a clear operational bottleneck.

From niche R&D to scalable operational drivers

In the early 2020s, many computer vision projects were isolated experiments – proofs of concept designed to test if a model could identify a specific defect or classify a document type. These initiatives were often siloed from core business systems, acting as passive monitors that generated alerts requiring human intervention. Today, the focus has moved decisively toward scalability and active participation.

A successful implementation is no longer defined merely by a model's accuracy on a controlled test set, but by its capacity to function reliably in real-world environments and take action. Where early systems simply flagged anomalies – creating queues of alerts for staff to review – modern architectures are capable of limited, safe autonomy. In high-confidence scenarios, the system doesn't just observe; it acts. This might mean automatically diverting a defective part on a conveyor belt or routing a verified invoice for payment without human touch. By shifting from simple alerting to intelligent decision support, organizations release human operators from routine triage, allowing them to focus only on complex edge cases where their expertise is truly required.

Identifying where visual automation adds genuine value vs. unnecessary complexity

Not every operational challenge requires a neural network. A critical maturity step for any organization is distinguishing between problems that can be solved with computer vision and problems that should be.

Unnecessary complexity often arises when visual AI is applied to tasks that are purely deterministic or binary. For example, simply detecting if an object is present on a conveyor belt is often better served by a low-cost photoelectric sensor than a high-bandwidth camera system. Over-engineering simple checks introduces needless maintenance overhead and data costs without delivering proportional value.

Genuine value emerges where the problem involves variability, context, or subjectivity. Is a scratch on a product "critical" or "cosmetic"? Is a pallet "unsafe" due to poor stacking or just "irregular"? Does a document layout imply a specific relationship between a total and a subtotal? These are qualitative judgments that previously required human intuition. Visual automation shines when it allows a machine to handle this nuance at scale, replacing subjective human estimation with consistent, data-driven reasoning.

The Core Value Triad: Speed, Consistency, and Scale

The business value of computer vision rests on three operational metrics: speed, consistency, and scale. By decoupling visual analysis from human limitations, organizations can maintain inspection standards at production speeds that exceed manual capabilities.

Overcoming Human Physiological Limits

Human vision is remarkable for its adaptability, yet it is physiologically ill-suited for high-speed, repetitive precision. Studies in industrial settings indicate that human inspection accuracy can degrade by 20% to 30% within just 20 to 30 minutes of repetitive tasks due to cognitive fatigue [Oxmaint. https://oxmaint.com/industries/facility-management/plumbing-pump-inspection-report-template]. While the human eye effectively processes visual data at a rate equivalent to 30-60 frames per second, modern Computer Vision systems can analyze 150+ frames per second with zero latency in decision-making [Sighthound. (2023) https://www.sighthound.com/blog/human-eye-fps-vs-ai-why-ai-is-better].

This capability gap enables Computer Vision systems to operate in environments that are physically impossible for human operators. Whether inspecting a web of steel moving at high speeds or detecting a sub-millimeter misalignment on a microchip assembly line, the system maintains the same level of precision at the end of a shift as it does at the start. It eliminates the "Monday morning" variance in quality control, ensuring that every unit is judged against an identical, unwavering mathematical standard.

The Tangible Cost of Quality Control Gaps

The financial implications of replacing statistical sampling with 100% inspection are measurable. In traditional workflows, quality control often relies on checking a small percentage of units and extrapolating results. This leaves an operational gap where defects can reach the customer. Deploying Computer Vision enables "total inspection," verifying every single unit without slowing production. This capability reduces the Cost of Poor Quality – which typically ranges from 15% to 20% of sales revenue for average performers [American Society for Quality (ASQ). https://asq.org/quality-resources/cost-of-quality] – by preventing expensive downstream costs like warranty claims, recalls, and reputational damage.

The "Hidden" Economics of Deployment

The sticker price of developing a Computer Vision model often represents only a fraction of the total investment required to sustain it. A common oversight in strategic planning is focusing solely on the initial training and integration costs while underestimating the ongoing operational realities. Sustainable deployment requires a broader economic view – one that accounts for the complete lifecycle of the system and recognizes the proprietary data it generates as an appreciating asset.

The TCO Equation

Effective budgeting requires analyzing the Total Cost of Ownership beyond the initial deployment. While hardware and model development constitute the visible capital expenditure, the long-tail operational costs often determine the project's financial viability. Significant resources are traditionally consumed by data annotation – which can account for 50% to 80% of a typical project's budget [Towards Data Science. (2025) https://towardsdatascience.com/computer-visions-annotation-bottleneck-is-finally-breaking/].

However, this "annotation tax" is rapidly evolving. New Verified Auto Labeling workflows, powered by Vision-Language Models, are shifting annotation from a manual bottleneck to a semi-automated batch process. By leveraging zero-shot detection for the majority of standard cases and routing only low-confidence predictions to human experts, organizations can reduce labeling costs by orders of magnitude. This shifts the economic model from paying for every bounding box to paying only for the validation of complex edge cases.

Beyond annotation, budgets must account for computational inference and storage. Additionally, models require continuous maintenance; without a budget for periodic retraining to address environmental changes (data drift), accuracy inevitably degrades, turning an asset into a liability.

The Data Flywheel Asset

Static models are a depreciating asset. In a production environment, variables shift: lighting changes, new product lines launch, and document formats evolve. Successful deployments treat the system as a dynamic learner rather than a fixed utility. This concept, known as the Data Flywheel, transforms daily operational friction into a source of continuous improvement.

When a human operator corrects a model's prediction – whether identifying a false positive on a line or correcting a field in an invoice – that data point is valuable. By capturing these corrections and feeding them back into the training dataset, the system adapts to the specific nuances of the organization. Over time, this accumulation of proprietary, validated data becomes a significant organizational asset, distinct from the commoditized models available to competitors.

The Evolutionary Leap: From "Perception" to "Reasoning"

For the past decade, computer vision has been largely defined by the ability to answer the question, "What is this?" Systems excelled at identifying discrete objects – counting items on a conveyor belt, spotting a helmet on a worker, or flagging a defect on a surface. While valuable, this capability, known as perception, represents only the initial stage of visual intelligence. The industry is now evolving towards reasoning, where systems not only identify objects but interpret the semantic relationships and broader context that give them meaning. For example, identifying a forklift and a worker in the same frame is perception; understanding that the worker is standing in the forklift’s blind spot while it reverses constitutes reasoning about spatial relationships and safety risk.

Phase 1: The Era of Perception

This phase was characterized by "bound-box" detection. Models like the YOLO (You Only Look Once) family became the industry standard for real-time applications, enabling systems to draw a box around an object and label it with a confidence score.

While effective for standardized tasks – such as counting bottles on a line or verifying that a safety vest is worn – this approach has limitations. Simple bounding boxes struggle with ambiguity. A model might successfully detect a "valve" but fail to determine if it is connected to a specific pipe without additional, often brittle, logic layers. It excels at inventory (what is present) but struggles with situation (what is happening).

Traditional Object Detection and Classification Limitations

Despite their speed, traditional detection models face significant limitations rooted in their "closed-set" nature. These systems can only classify objects they were explicitly trained to recognize. If a production line introduces a new component variant, or if a defect presents in a novel way not represented in the training dataset, the system remains blind to it. This rigidity forces organizations into a continuous cycle of data collection and retraining just to maintain baseline performance when variables change.

Furthermore, these models output raw data – coordinates and class probabilities – rather than actionable insights. Determining relationships between objects requires engineers to build fragile layers of hard-coded logic on top of the model. For instance, detecting a "bottle" and a "cap" is straightforward for a CNN, but confirming the cap is threaded correctly often requires complex, custom heuristics that break easily if the camera angle shifts or lighting changes. This dependency on manual logic layers makes scaling "perception-only" systems notoriously difficult and expensive to maintain.

Phase 2: The Era of Visual Reasoning

The current phase is defined by the integration of vision with language models, often referred to as Large Vision-Language Models (LVLMs). These systems do not rely solely on fixed categories defined during training. Instead, they leverage semantic understanding to interpret visual data.

This unlocks zero-shot capabilities, where a system can identify objects or conditions it has never explicitly seen before, simply by processing a text description. In a logistics scenario, instead of retraining a model with thousands of images to recognize a new packaging label, an operator can simply prompt the system to "find the red package with the hazard symbol." This flexibility drastically reduces the deployment time for new use cases and allows the system to adapt to changing environments without constant retraining.

Semantic Context and Zero-Shot Capabilities

The core innovation of this phase is the shift from "closed-set" classification to "open-vocabulary" detection. Traditional models treat objects as isolated categories; they do not inherently understand that a "dented box" and a "torn box" share the concept of "damaged packaging." Vision-Language Models possess this semantic awareness. They can decompose a scene into attributes (state, texture, shape) and relationships, enabling them to interpret complex visual queries.

This semantic depth powers "zero-shot" detection – the ability to identify objects or conditions the model has never explicitly seen during training. By altering a text prompt, operators can dynamically adjust the system's focus – for example, shifting from detecting "vehicles" to specifically flagging "trucks with open cargo doors" – without writing a single line of code. This capability is critical for addressing the "long tail" of operational edge cases: rare, unpredictable events that lack sufficient training data but can be easily described in natural language.

Bridging the Gap: Applying CV to Documents

While Computer Vision is most intuitively associated with physical operations – autonomous vehicles, manufacturing lines, and security feeds – its application to document processing is equally transformative. To a neural network, a scanned invoice is not fundamentally different from a photograph of a warehouse floor; both are simply grids of pixels containing shapes, textures, and spatial relationships.

However, while the raw input is identical, the nature of the data differs. A warehouse scene consists of physical objects in 3D space, whereas a document is a dense, 2D representation of symbolic logic. To extract reliable insights, the analysis must adapt to this complexity, treating the page not merely as a container for text, but as a structured visual environment where layout and position are critical for interpretation.

Treating Documents as Visual Scenes

Traditional Optical Character Recognition often treats a document as a linear stream of text, stripping away the spatial formatting that provides essential context. By contrast, treating a document as a "visual scene" means applying computer vision techniques – such as object detection and semantic segmentation – to the page layout itself.

Just as a model identifies a car on a road, it identifies a "table," a "header," or a "signature block" on a page. This approach recognizes that the meaning of data is often defined by its position and visual hierarchy: a number is interpreted as a "Total" not merely because of the digits it contains, but because it sits at the bottom right of a column, often emphasized by a horizontal line or bold typography. By analyzing the geometry of the page, the system reconstructs the logical structure that linear text extraction ignores.

Parallels Between Manufacturing Defects and Administrative Processing

The cognitive process required to audit a document mirrors the logic used in industrial quality control. Just as a vision system on an assembly line flags a missing component or a misaligned label, a document vision system detects administrative anomalies. A contract missing a signature is functionally identical to a product missing a bolt – both are "incomplete units" that pose a downstream operational risk.

Similarly, spotting a discrepancy between a date on a purchase order and an invoice parallels detecting a color inconsistency in a batch of textiles. In both cases, the system is not just reading data; it is validating the integrity of the object against a standard model of "correctness." By applying the rigorous anomaly detection frameworks of manufacturing to administrative workflows, organizations can automate quality control for data, preventing clerical errors from compounding into financial liabilities.

Breaking the "OCR Wall": Visual RAG and Document Intelligence

For decades, the standard paradigm for document processing has been linear: rasterize, perform Optical Character Recognition, and serialize the output into a string. This workflow functions on the implicit assumption that the text contains the signal while the layout is merely presentation. While sufficient for plain prose, this assumption fails when applied to complex enterprise documents – engineering schematics, financial tables, and Piping and Instrumentation Diagrams (P&IDs) – where meaning is encoded in geometry as much as in characters.

The emergence of Visual Retrieval-Augmented Generation offers a mechanism to breach this "OCR Wall." By shifting from text-centric pipelines to visual-first methodologies, modern architectures can embed and retrieve information based on visual features directly. This enables systems to reason across the full semantic and spatial context of a document, preserving the critical relationships that traditional serialization inevitably discards.

The "Dark Matter" of Enterprise Data

A vast proportion of institutional knowledge remains inaccessible to standard retrieval systems, locked within formats that resist simple digitization. Often referred to as "dark data," this information resides in complex layouts – engineering drawings, multi-column financial reports, and annotated diagrams – where the semantic value is derived from spatial orientation rather than linear sequence. Because traditional indexing pipelines are architected for continuous text streams, they effectively render this geometrically structured data invisible to downstream analytics.

Why Standard OCR Fails on Spatially Complex Documents

Standard OCR engines are optimized for the sequential reading order of natural language, forcing a left-to-right, top-to-bottom serialization of content. This rigid approach destructively flattens the structure of complex documents where geometry dictates meaning.

In engineering documents like Piping and Instrumentation Diagrams (P&IDs), meaning is defined by connectivity rather than linear sequence. A valve icon positioned "above" a pipe segment denotes a specific flow control relationship. However, traditional extraction parses these elements as disjointed text fragments – or ignores the non-textual graphic entirely. The result is a "bag of words" output where component tags (e.g., C-101, V-202) are captured, but the connectivity logic that defines the system is obliterated.

This failure extends to standard multi-column layouts. A naive engine frequently ignores column dividers, reading directly across the page – concatenating line n of Column A with line n of Column B. This "layout scrambling" destroys the semantic flow, merging distinct paragraphs into coherent-looking but nonsensical sentences. The resulting text stream contains the correct characters but falsifies the information, feeding downstream models corrupted data that inevitably leads to hallucinations.

The Cost of Lost Spatial Context

The conversion of 2D documents into 1D strings strips away the coordinate system that anchors data. This "spatial amnesia" renders RAG systems ineffective for structured queries. When a financial table is flattened, the explicit relationship between a cell value (e.g., "$4.2M") and its corresponding headers (e.g., "Q3 Adjusted EBITDA") is severed.

Consequently, the embedding model places the data point in vector space based on its immediate textual neighbors rather than its structural hierarchy. When a user queries the system, the retrieval mechanism may find the number, but the LLM lacks the structural context to attribute it correctly. This leads to a specific class of failure where the model retrieves the correct source document but still hallucinates the answer, unable to bridge the gap between the raw text and the table's logical schema.

Architecture A: The Pipeline Approach (Extract-Then-Embed)

This architecture treats document understanding as a sequential engineering process, often referred to as modular RAG. Rather than feeding a raw image directly into a large reasoning model, the pipeline decomposes the document into its constituent parts – headers, paragraphs, tables, and figures – using specialized, smaller models. This modularity allows for granular optimization at each step, enabling engineers to debug and improve specific stages (e.g., table extraction) without retraining the entire system.

Mechanics: Layout Analysis Models + Enhanced OCR

The foundation of this architecture is a dedicated Document Layout Analysis model, typically a fine-tuned object detector (e.g., YOLO or Mask R-CNN). Unlike naive OCR that blindly scans pixels, this stage first "sees" the page structure, drawing bounding boxes around semantic regions such as titles, text blocks, tables, and figure captions.

Once the layout is segmented, the pipeline applies "Enhanced OCR" strategies. Text blocks are processed with standard engines, while complex regions like tables are routed to specialized algorithms that reconstruct the row-column structure into Markdown or HTML. This two-step process – detect, then read – ensures that the final output preserves the logical hierarchy of the original document, converting a visual layout into a structured schema (like JSON) rather than a chaotic stream of characters.

The Role of Text Embeddings in the Pipeline

Once the document is converted into a structured format – typically Markdown or JSON – the system moves to the embedding phase. Unlike the "bag of words" approach, the layout metadata allows for semantic chunking. Instead of arbitrarily slicing text based on token counts, the pipeline can group headers with their corresponding paragraphs and table rows with their column definitions before vectorization.

These structured chunks are then processed by standard text embedding models. By maintaining the logical association between a label and its data during the chunking process, the resulting vectors retain a stronger semantic signal. This ensures that when a user searches for specific criteria, the retrieval system surfaces the complete context of the answer, rather than a fragmented sentence stripped of its governing header.

Ideal Use Cases: Deterministic Control and Speed

This architecture is the preferred choice for high-volume, regulated environments where traceability and latency are paramount. Because the computational heavy lifting of extraction occurs upfront during ingestion, the actual query retrieval phase is lightweight, fast, and cost-efficient.

It excels in scenarios requiring deterministic control. Unlike end-to-end neural approaches that can be "black boxes," a pipeline approach allows engineers to audit every step. If an answer is incorrect, the failure can be traced to a specific extraction error or chunking strategy. This transparency makes it indispensable for financial auditing, insurance claims processing, and legal discovery, where the ability to verify the exact lineage of a data point is a strict compliance requirement.

Architecture B: The Native Multi-Modal Approach (ColPali/Vision-LLMs)

While the pipeline approach attempts to structure visual data into text, the native multi-modal architecture operates on the premise that the image is the data. These systems, exemplified by models like ColPali and advanced Vision-Language Models (VLMs), abandon the separation between "seeing" and "reading." Instead of converting documents into intermediate text formats, they process the visual representation of the page directly, embedding the image itself into a high-dimensional vector space that captures both semantic content and spatial layout simultaneously.

Mechanics: Direct Visual Embedding and Patch-Based Retrieval

In this architecture, the document page is treated as a high-resolution image input. The system utilizes a vision encoder (typically a specialized Transformer like SigLIP or ViT) to divide the image into a grid of fixed-size "patches" – effectively visual tokens. Each patch is independently projected into the embedding space, resulting in a multi-vector representation for a single page.

Crucially, this process changes how meaning is derived. The model does not "read" text letter-by-letter; instead, it recognizes visual concepts. Much like a human driver instantly understands a red octagon means "Stop" without spelling out S-T-O-P, the model recognizes the visual shape of a table, a diagram, or a specific price tag (e.g., "$500") as a semantic entity. It treats text, charts, and logos as "visual hieroglyphs," mapping their pixel patterns directly to conceptual vectors. This allows the system to understand that a specific grid of lines is a "pricing table" purely by its shape, capturing context that linear text extraction would miss.

Retrieval relies on "late interaction" mechanisms (similar to ColBERT). Instead of compressing the entire page into a single vector, the model retains the embeddings for all visual patches. When a query is issued, the system computes similarity scores between the query tokens and the specific visual patches that contain the answer. This allows the model to "attend" to precise regions – matching a user's question directly to the pixels of a specific cell row or diagram component.

Bypassing Intermediate Text Conversion

Eliminating the OCR step removes the primary source of noise in document intelligence: cascading errors. In a traditional pipeline, if the OCR engine misinterprets a pixelated "8" as a "B," or if the layout parser merges two distinct columns, that error is hard-coded into the text stream before the reasoning model ever sees it. This creates a "Game of Telephone" effect where semantic fidelity degrades at every handover between models.

By embedding the visual data directly, the system preserves the raw signal. The model retains access to original fonts, colors, and spatial alignments – features that text converters strip away. If a document contains a faint watermark, a color-coded status (e.g., red for "Urgent"), or a handwritten annotation, the vision model incorporates these features into the embedding. This "end-to-end" approach ensures that the retrieval system reasons on the ground truth of the document, rather than a degraded, text-only approximation.

Ideal Use Cases: Context-Heavy Reasoning and Complex Queries

This architecture is the superior choice for heterogeneous, unstructured data where the information density is visual rather than textual. It is specifically designed for Visual Question Answering (VQA) scenarios where the answer cannot be found in the text alone but requires interpreting the composition of the page.

For example, in engineering, if a user asks, "Which valve isolates the backup pump?", the answer lies in the schematic lines connecting the symbols, not in the labels themselves. A text pipeline would return a list of valve names; the vision model traces the pixel path to identify the correct component. Similarly, in financial analysis, a query like "Show me the quarter with the steepest decline" requires the model to interpret the slope of a trend line in a bar chart – a task impossible for systems that only ingest raw numbers.

The Engineering Trade-off Matrix

Choosing between a modular pipeline (Architecture A) and a native multi-modal system (Architecture B) is rarely a question of which model is "smarter." Instead, it is a calculation of system constraints: how much latency can the user tolerate? What is the budget for storage? Is the workflow real-time or batch-oriented? There is no silver bullet; the correct architecture is determined by where the bottleneck lies in the specific operational environment.

Comparing Latency, Cost, and Accuracy for Batch vs. Real-Time

The decision ultimately rests on the "Iron Triangle" of engineering: speed, cost, and quality.

Latency Profiles:

- Real-Time (Architecture A): Standard vector search is nearly instantaneous (milliseconds). This architecture is mandatory for high-concurrency applications, such as customer-facing chatbots, where response time directly correlates with user satisfaction.

- Batch/Analyst (Architecture B): Because the system performs complex "late interaction" scoring (comparing query tokens to thousands of image patches), retrieval is slower. This latency (often seconds rather than milliseconds) makes it less suitable for public interfaces but acceptable for "human-in-the-loop" expert workflows – such as an engineer reviewing a P&ID – where accuracy is prioritized over instant speed.

The Storage Penalty: The most significant operational difference lies in index size. Architecture A (Text Pipeline) compresses a page into a few dense vectors – a negligible storage footprint. Architecture B (Native Multi-Modal), which stores thousands of patch vectors per page, explodes index size by orders of magnitude (often 50x–100x). This requires significantly more RAM and VRAM to serve, making it the more expensive option for massive archives.

The Accuracy Divide: For plain text contracts or policy documents, Architecture B is often "overkill" – burning GPU hours to "see" simple ASCII characters. However, for visually dense data (charts, schematics), Architecture A’s speed becomes irrelevant because its accuracy drops to near zero. The optimal strategy often involves a hybrid routing approach: using lightweight text models for standard queries and routing complex, visual requests to the heavy multi-modal engine.

Engineering Reality: Hallucinations, Hardware, and the Edge

Moving from architecture diagrams to production environments reveals the friction points of modern Computer Vision. Theoretical capabilities often collide with hard constraints: probabilistic models that confidently lie, video streams that saturate bandwidth, and the perennial shortage of labeled training data. Deploying these systems requires managing the trade-offs between stochastic model behavior and the deterministic reliability required by enterprise applications.

The Hallucination Problem in Visual AI

While "hallucination" is a well-known phenomenon in text LLMs, Visual-Language Models introduce a unique and often more dangerous variant: visual grounding failure. Unlike a text model that invents facts from its training weights, a vision model can "look" at a clear image and confidently misidentify an object, misread a number, or detect a relationship that does not exist.

This is not merely a generation error; it is a perception error where the model's vision encoder and language decoder fail to align on the same reality. The vector representation of the visual features may not map cleanly to the specific text tokens required, causing the language component to "fill in the blanks" based on probability rather than the actual pixels present. The model effectively prioritizes its linguistic training data over the visual evidence, describing what it expects to see rather than what is actually there.

How Vision-LLMs "Invent" Data

This creates a necessary paradox in engineering decisions. Native Multi-Modal models are superior for capturing context and topology – understanding that a red line means "danger" or that a slope indicates "decline." However, this strength is also the source of their specific failure mode: they prioritize concepts over characters.

While these models excel at interpreting the "gestalt" of a page, they struggle with high-frequency details. Because the vision encoder processes images in fixed-size patches (e.g., 14x14 pixels), fine-grained data like serial numbers, coordinates, or dense financial figures can get compressed into a single, blurry vector.

When the model encounters this ambiguity, it does not output "I can't read this." Instead, the language decoder – trained to predict the next plausible token – hallucinates the most statistically likely value. It might correctly identify a string as a "date" based on its visual shape cloud(DD/MM/YYYY) but, unable to resolve the blurry digits, fills them in with a random recent year.

Essentially, where standard OCR fails by scrambling the layout, Vision-LLMs fail by smoothing the reality. They can generate a perfectly coherent, logical, and visually grounded answer that is numerically false – a "vibes-based" interpretation that captures the spirit of the document while inventing its facts.

Confidence Scoring and Constraints

To tame the creative tendencies of Vision-LLMs, engineers must impose strict boundaries on the generation process. The most effective method is constrained generation (or "guided decoding"), where the model's output is forced to adhere to a predefined schema, such as JSON or a specific Regular Expression (Regex).

By restricting the vocabulary – for example, forcing the model to output only digits for a "price" field – we physically prevent the language decoder from hallucinating prose or irrelevant commentary. If the visual features are ambiguous, the model cannot revert to "chatty" filler text; it must either find the best numerical fit or fail explicitly.

Furthermore, token-level confidence scoring acts as a crucial quality gate. Unlike a simple binary "true/false" flag, modern inference engines allow access to the log-probabilities of every generated token. If the probability of a critical digit (e.g., the "3" in "300 psi") falls below a set threshold (e.g., 95%), the system should automatically flag the record for manual review. This approach shifts the workflow from "trusting the AI" to "auditing the edge cases," ensuring that low-confidence predictions never enter the production database silently.

Human-in-the-loop Triaging

Complete automation in high-stakes environments is a dangerous fallacy. Instead, resilient systems utilize a probabilistic routing layer. This mechanism uses the confidence scores derived during generation to sort document flows into two streams: Straight-Through Processing and Exception Handling.

Documents or specific data fields that exceed a high confidence threshold (e.g., >98%) bypass human intervention entirely, maximizing throughput. However, any data point falling into the "ambiguity zone" is automatically routed to a verification queue.

Crucially, the interface for this review must be visually grounded. The human operator should not merely see a text field to edit; they must be presented with the specific crop of the original image (the bounding box) alongside the model's prediction. This allows for rapid, glance-based verification.

These corrected exceptions then feed the data flywheel. By saving the human corrections back into the training set, engineers target the specific patterns that confuse the model. As the system is fine-tuned on these difficult edge cases, its internal confidence for similar data points increases. Over time, this drastically reduces the volume of the verification queue, shifting human effort from routine oversight to handling only novel, unforeseen anomalies, while the vast majority of processing becomes fully autonomous.

The "Duty Cycle" Decision: Cloud vs. Edge

One of the most frequent architectural failures in deploying Visual AI is treating video streams like text logs. Text is lightweight; sending a million JSON lines to the cloud is trivial. Video, however, is a deluge of data. A single 1080p stream can generate gigabytes of data per hour, saturating uplinks and incinerating cloud storage budgets.

The fundamental engineering decision here is the Duty Cycle: What percentage of the time does the system need to be "eyes-on"? The architecture that works for processing a few thousand insurance claims per day (low duty cycle, high latency tolerance) will catastrophically fail if applied to a factory floor safety system monitoring 50 cameras 24/7. Distinguishing between "forensic" (looking back) and "real-time" (looking now) requirements dictates whether the compute should live in a distant data center or right next to the camera sensor.

The Bandwidth Trap of 24/7 Video

For engineers accustomed to the "infinite scale" of the cloud, video data provides a harsh reality check. The math of continuous streaming is brutal: a single 1080p camera running at 30 frames per second requires approximately 5–8 Mbps of sustained upload bandwidth.

Scaling this to a standard industrial deployment – say, 50 cameras monitoring a warehouse – creates a requirement for hundreds of Megabits per second of dedicated upstream capacity. Attempting to pipe this raw footage to a cloud inference endpoint (like ChatGPT or Gemini) for real-time analysis is functionally impossible for two reasons:

- The Cost Wall: Cloud vision models bill by the image or second. Processing 30 frames per second, 24 hours a day, results in millions of API calls per camera, per day. The bill for a single month of continuous "cloud vision" often exceeds the cost of the facility it is monitoring.

- The Latency Spike: Relying on the public internet for safety-critical logic introduces unacceptable jitter. If a forklift is about to collide with a shelf, the round-trip time (RTT) to a data center, plus inference queue time, creates a lag of seconds. In the physical world, a 2-second delay is the difference between a "near miss" and a catastrophic accident.

Therefore, the architecture must shift from "streaming everything" to "streaming events." The goal is not to send the video to the model, but to bring the model to the video.

Hardware vs. Cloud APIs

The solution to the bandwidth trap lies in a Hybrid Edge-Cloud Architecture. Instead of treating the cloud as the primary eye, we deploy local edge compute devices – such as NVIDIA Jetson, Raspberry Pi with Hailo accelerators, or dedicated NPU modules – directly on the network rim.

These edge nodes perform the "dumb but fast" labor. They run lightweight, optimized detection models (like YOLO or EfficientDet) to filter the visual noise. Their job is not to reason, but to trigger. For example, an edge device watches a loading dock 24/7. It discards 99.9% of the footage where nothing happens. Only when it detects a specific trigger – motion in a restricted zone, or a specific object class – does it capture a single high-quality frame.

This single frame is then dispatched to the Cloud API (Architecture B). Here, the heavy, expensive VLM applies its reasoning capabilities to answer complex questions: "Is the person in this image wearing a hard hat?" or "Read the license plate on this truck."

This split is the economic unlock for scalable vision systems:

- Edge (Local Hardware): Handles high-frequency, low-latency detection ($0 marginal cost per second).

- Cloud (API): Handles low-frequency, high-intelligence reasoning (pay-per-use).

By moving the filter to the edge and keeping the intelligence in the cloud, engineers reduce bandwidth consumption by orders of magnitude while retaining the ability to deploy state-of-the-art reasoning on the events that actually matter.

The Sovereign AI Alternative: Owned Models & Private Cloud

While the Hybrid Edge-Cloud architecture optimizes costs, relying on public APIs like Gemini or ChatGPT introduces external dependencies: data privacy risks, variable latency, and "rented intelligence." For enterprises handling sensitive IP or operating in regulated industries, sending visual data to a third-party provider is often a non-starter.

This drives the case for Sovereign AI: deploying open-weights models (like LLaVA, Qwen-VL, or Pixtral) on your own infrastructure. By hosting these models on private cloud instances or on-premise GPU clusters, organizations regain total control. This approach eliminates per-token pricing – replacing it with fixed hardware costs – and ensures that no pixel ever leaves the company's secure perimeter. While the initial engineering lift is heavier, "owning the weights" allows for specialized fine-tuning that generalist APIs cannot match.

The Cold Start & Data Scarcity

The most common roadblock in deploying a custom Visual AI system is not selecting the model, but feeding it. Unlike text, where companies sit on terabytes of documents, high-quality, labeled visual data is often nonexistent. A manufacturing plant might want to detect a specific defect that only happens once a month. A logistics company wants to track a new package label that hasn't been printed yet. This is the Cold Start Problem: How do you train a system to recognize something it has never seen, or has seen only a handful of times?

Bootstrapping with Synthetic Data

When real-world data is unavailable or expensive to collect, the most effective engineering workaround is to manufacture it. Synthetic Data Generation flips the traditional pipeline: instead of collecting images and manually annotating them, engineers define the parameters of the scene and programmatically generate perfectly labeled datasets.

For geometric or rigid objects – such as industrial parts, retail packaging, or architectural layouts – 3D rendering engines (like Unity, Unreal Engine, or NVIDIA Omniverse) are invaluable. If a factory needs to detect a rare structural fracture that occurs in only 0.01% of units, waiting to collect enough real examples would take years. Instead, engineers can take a CAD model of the part, digitally apply the texture of the fracture, and render thousands of images from different angles, lighting conditions, and backgrounds.

The "killer feature" of this approach is automatic annotation. Because the computer generates the image, it knows the exact pixel coordinates of every object. There is no need for human labelers; the simulation outputs the image and its corresponding bounding box or segmentation mask simultaneously, creating a "perfect ground truth" dataset that allows the model to learn the feature's topology before it ever sees a real camera feed.

Active Learning Workflows

Synthetic data gets the system off the ground, but real-world nuance eventually requires real-world examples. The mistake most teams make is attempting to label everything – dumping thousands of hours of video into a labeling queue. This is not only cost-prohibitive but statistically inefficient, as the vast majority of frames contain redundant, easy-to-learn information.

Active Learning solves this by inverting the selection process. Instead of humans choosing what to label, the model chooses for itself.

- Inference & Uncertainty Sampling: The initial model (perhaps bootstrapped with synthetic data) runs over the raw, incoming data stream.

- The "Confusion" Filter: The system discards the 95% of images where it is confident. It flags only the edge cases – the blurred shadows, the occluded objects, or the novel angles – where its confidence score drops below a specific threshold.

- Targeted Annotation: Only these high-uncertainty samples are sent to human annotators.

- Iterative Retraining: The model is retrained on this highly curated "curriculum" of difficult examples.

2026 Perspectives: The State of the Art

By 2026, the focus in Computer Vision has moved from capability to reliability. The novelty of models that can "see" has been replaced by the engineering challenge of deploying them at scale. We are no longer asking if a system can interpret a chart or a video feed; the questions now revolve around latency budgets, hardware costs, and standardized retrieval patterns. The field has matured into a predictable set of architectural choices, moving away from bespoke experiments toward established infrastructure.

The Rise of Hybrid Architectures

The industry has moved past the binary choice between "OCR pipelines" (Architecture A) and "Native Vision" (Architecture B). In 2026, the dominant design pattern becomes the Hybrid Multi-Stage RAG, which treats the selection of a processing engine as a dynamic routing problem rather than a static architectural commitment.

These systems employ a lightweight "traffic controller" model at the ingestion point. A page dominated by standard prose – such as a legal contract or an email thread – is routed to the traditional, cost-effective text pipeline. Conversely, if the controller detects high visual density – such as a P&ID schematic, a slide deck, or a financial table – it shunts that specific page to the Vision-VLM track.

This approach optimizes the cost-performance curve by mirroring "System 1 / System 2" cognitive processing. Enterprises can process the bulk of their archives using the speed and low storage footprint of text indices, while automatically reserving heavy, expensive GPU compute for the complex visual reasoning tasks that strictly require it. The architecture is no longer about choosing the "best" model, but about orchestrating the right model for the specific asset.

Hardware Commoditization and NPUs

In 2026, the barrier to entry for running complex vision models has collapsed due to the ubiquity of the Neural Processing Unit. What was once specialized silicon reserved for high-end servers or niche industrial gateways is now a standard component in consumer electronics. From "AI PCs" with dedicated inference cores to security cameras with onboard acceleration, the hardware capable of running quantized Small Language Models and vision encoders is everywhere.

This commoditization has decoupled "intelligence" from "connectivity." Engineers can now deploy sophisticated detection and reasoning logic directly onto the endpoint – be it a drone, a tablet, or a workstation – without requiring a tether to the cloud. The challenge has shifted from procuring expensive GPUs to optimizing models (via quantization and pruning) to fit within the thermal and memory constraints of these edge devices. The NPU is effectively the new Floating Point Unit: a standard, expected part of the compute substrate that makes visual intelligence a local primitive rather than a remote service.

The Standardization of Visual RAG Patterns

The experimental methods of embedding images into vector stores have consolidated into a robust design pattern known as Visual RAG. By 2026, the industry has largely deprecated the practice of OCR-ing images solely for the purpose of indexing. Instead, the standard workflow treats the visual data itself as the primary indexable entity.

Modern vector databases now treat multi-modal embeddings as first-class citizens. The unit of retrieval has shifted from a "text chunk" to a "visual patch." When a user asks a question, the system does not scan hidden text layers; it scans the high-dimensional vector space of the document's visual layout. This allows for semantic retrieval based on visual concepts – finding a "wiring diagram" or a "handwritten note" based on their visual signature rather than their keywords.

Crucially, the user interface patterns have standardized around provenance. In 2026, a generative answer is considered incomplete without strict visual grounding. "Visual Citations" are mandatory: every assertion made by the model is hyperlinked not just to a page number, but to a specific bounding box on the source image. This closes the trust loop, allowing users to instantly verify the AI's interpretation against the raw pixels of the original document.

–

Mapping the industry's trajectory is distinct from navigating the engineering reality. The gap between a functional prototype and a production-grade system is defined by thousands of specific architectural choices – from selecting the right NPU for your thermal constraints to designing a retrieval pipeline that balances cost with semantic precision. As these systems migrate from the lab to the critical path, the challenge is no longer just accessing intelligence, but orchestrating it reliably within the stubborn constraints of the real world.

Partner with us for Serious Results

Realizing the potential of Visual AI requires more than just model access. It demands a pragmatic approach to infrastructure – one that respects bandwidth limits, systematically mitigates hallucination risks, and integrates seamlessly with existing workflows. We focus on turning "stochastic magic" into reliable business processes. If you are ready to move beyond proofs of concept and build visual intelligence into your critical path, let’s have a conversation. We can audit your current data landscape, assess your infrastructure constraints, and map a deployment strategy that delivers measurable impact.